Dark Buddha

Moral Responsibility in Apocalypse Now

by Eric Pettifor

In exploring the question of 'insanity' in Coppola's Apocalypse Now, I will leave the DSM-IV in the kitchen with the other cookbooks, and make recourse to an older framework for the definition of insanity, one where insanity is essentially an impairment of personhood, and where personhood is defined in terms of the trilogy of mind (cognition, affect, and agency). Taking off from the ethico-legal perspective (Paranjpe, 1993) I will argue that there is no insanity as such in the film Apocalypse Now (Coppola, 1979), even though both parties using the label in the film, the military and Colonel Kurtz, try to accuse each other of it, and I think it's the Coppola's intention to have us believe that it is the military who is really insane.

However, the failure portrayed in the film is primarily a moral failure. Even taken to an extreme, can it be called insanity? If so, there are great many people in our prisons who ought not to be there, but rather in a mental hospital.

This is not to say that there are not instances in the film of behaviour which could be characterized as such. The film starts with a jungle which bursts into flames, helicopters flying everywhere, and all this superimposed on the upside down face of Captain Willard lying in bed. Willard gets up, does some moves reminiscent of drunken Tai Chi, then smashes a mirror with his fist.

Clearly he is stressed out to the point of having a psychotic episode, but from the narration we might be led to believe that the stress isn't from jungles bursting into flame, but rather from inaction, waiting in that hotel for a week to receive an assignment. Once he has it he functions precisely, and we see why he was chosen for the assignment. From the military's perspective, he is a precision instrument.

A character who may be certifiable is the surfing Colonel in charge of the air cavalry. He seems to be out of touch with reality. Kurtz advocates making friends with "the horror", which is excessive, but a regard and recognition for the reality of it would seem to be essential, especially for one continuously confronted with it. However, the Colonel is quite oblivious to it, encouraging soldiers to surf in the midst of heavy battle. Yet he seems to be very well adapted to his situation, efficacious, an inspired leader. He notes with regret that "Some day this war's going to end," but one gets the impression that he is career military and that he will always have a venue in which to play since the U.S. military is seldom idle, always finding some part of the world in which to act. In terms of the trilogy of mind, that which is most impaired is affect, or feeling. He characterizes the girl who drops a grenade in a helicopter as a "barbarian", and vengefully goes after her and kills her from the air, whereas his own actions, flying in with 'Flight of the Valkries' playing and engaging in rapid mass slaughter is civilized. He is virtually devoid of compassion, as we see when his attention is easily diverted, on hearing that Lance the famous surfer is present, from a soldier whose guts are spilling out and whose virtue he was moments before dramatically extolling. He may indeed be insane, and given that he is well adapted to his circumstance, we might wish to argue that the military which has created this circumstance must be insane. I think this is Coppola's intention. However, those at the top making executive decisions leading to such circumstances bear more responsibility than the pieces they move in the field. The issue at that level still seems to be one of moral responsibility.

Moral responsibility is intimately connected to feeling since once all the philosophical rationalization of ethics are reduced and the evolutionary psychologists' concern with reciprocal altruism perpetuating genes is dismissed as inadequate, it is feeling which evaluates good and bad, right or wrong. The relationship between feeling and insight is critical as well, and here we may be getting into territory which is beyond trilogy of mind as we move farther up the river closer to Kurtz, closer to Buddha.

This defines the aesthetic of the latter part of the film. Kurtz values clarity, honesty, the ability to see things clearly, even "the horror". This insight is light, "the horror" the dark.

This is most extreme in the representation of Kurtz himself. We never really see him in full daylight, only in stark contrast, his bald head emerging from the darkness, almost as enigmatic as the stone Buddha's. Indeed, Willard's first audience with Kurtz is composed like a worshipper in a temple, and a scene of Kurtz reading dissolves into an extreme close-up of the Buddha's lips, as if to say, 'From the lips of the Buddha'.

At first the association with Buddha was a bit puzzling. This film is not Little Buddha or 7 Years in Tibet! I had wondered if perhaps Coppola was making use of the stone images simply for the sake of atmosphere. He is compelled by aesthetic, which is one of the very first things that strikes one about this film. It is beautiful. Perhaps he is just playing with extremes for a purely visual effect.

Two other instances of this extreme light and darkness that appear pre-Kurtz are the Playboy Bunny show and the hotly contested bridge upriver.

In both instances Coppola is dealing with extremes. In the first is one example of many throughout the film of the banal contrasted with the reality, often horrific, of the situation, and with the underlying tension which cannot be adequately masked by conventional forms from home. At the bridge he is presenting something a little closer to reality, and even more ugly, but at the same time, as the character of Lance, stoned on acid, observes, "beautiful". Yet one of the desperate men struggling through the water welcomes them to "the asshole of the world"! Perhaps one has to be stoned on acid or sitting comfortably watching a film of it to see the beauty.

To the extent that Kurtz is insane it is because he is caught up by, possessed by "the horror". It can be quite compelling in its power, and it is this, I think, to which Coppola applies his genius, not just an aesthetic overindulgence. It's critical in assessing ultimately what happened to Kurtz.

There are really two directions from which to approach the question of Kurtz' sanity, or lack thereof; that of the situation Willard discovered, and the reasons the military considered him insane. They aren't necessarily the same. In considering Kurtz' sanity at the point in time of his encounter with Willard I think it's important to strip away the exotic aesthetic and locale and consider if a serial murderer in our society cut off the heads of his victims for display purposes, would he necessarily be insane? This isn't entirely fair, since the context is important, especially as a precursor, but it's necessary in order to get past the aesthetic to the issue of moral responsibility. From the ethico-legal perspective in association with the trilogy of mind, if Kurtz was defective in cognitive, affective, or volitional terms then he cannot be held responsible, essentially 'not guilty by reason of insanity', impaired personhood.

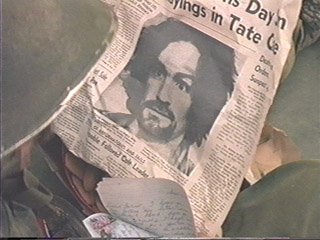

The serial murderer that Coppola visually alludes to is Charles Manson . Both Kurtz and Manson had cult followers who regarded their leader as semi-divine and who engaged in activities which from the broader perspective outside the immediate context of the participants appear to be anti-social in the extreme. If Manson was insane, then so was Kurtz. And so were all of their followers. And so, perhaps, is religion.

We find ourselves in a very complicated, very grey region, quite unlike the sharp contrast of the film. This is the territory of charismatic leaders and manipulation and appeal to a higher power which is a tool for manipulation as well as a facilitating environment whose effect influences even the charismatic leader. In short, it is a domain of everyday life - in politics, advertising, religion - any social environment where you find humans manipulating other humans.

Sometimes it seems that the dividing line in this area between sane and insane is simply the point at which we get really grossed out or begin to feel personally threatened. However, this inclination is not necessary for the defense of society. We can consider moral responsibility in terms of social interest without recourse to the label of insanity, which in this context is simply an admission of our inability to comprehend certain actions, and the fear and repulsion we feel in response to them. It has to do with us, not with the actors. In instances where the actors are not cognitively, affectively, or agentically incapacitated, I think it is better to consider moral responsibility than to resort to the label of insanity. And I think that both Manson and Kurtz knew what they were doing.

Kurtz claims that the military is insane, especially in regard to their charge of murder for his unauthorized execution of three double agents. The military says that Kurtz is insane, but their concern seems to be effectively desertion, as Kurtz as unilaterally extricated himself from the chain of command. He's still killing as he did when he was working within the system, the issue is not so much with the actions themselves. Indeed, from a trilogy of mind perspective he seems to be displaying a little too much agentic independence for the military's taste! We learn from Willard's perusal of his notes that even the murder charges would have been dropped if he had agreed to come back to the fold.

Kurtz' charge that the military is insane is too extreme, but clearly there is something wrong. He notes that they train young men to kill, but that they can't paint the word "fuck" on the side of their airplanes, as that would be obscene. This sort of contradiction is even better illustrated by the boat's crew massacring a boatload of Cambodians when a young woman makes a sudden move which turns out only to have been to protect a puppy. Innocent civilians can be killed without authorization, but not double agents?

Basically, war flagrantly violates conventional morality and at best can only be regarded as a necessary evil (if that), but these acts are all rationalized away or dismissed in order to preserve a veneer of civilization which is ultimately a lie in the face of the reality, "the horror". It seems to me that it is Copolla's intention to have us ultimately be on the side of Kurtz and his heir Willard, who through an acknowledgement and experience of "the horror" deliver an anti-war message stronger than any slogan. But in characterizing the military as insane, insanity is being used as a term for something we don't like, a pejorative, and again I would argue that the failure of morality, blatant or masked by rationalization, is insufficient to justify the label.

And how could the Buddha be insane? While a brief visual reference to Manson is made in the film, the association with Buddha is much stronger in the cinematographic associations of Kurtz and later Willard with the stone image, and with Kurtz' occupation of a temple compound, himself ensconced at the top, his followers, and the corpses, below. I think many Buddhists would be somewhat uncomfortable with the association, especially with all the corpses and severed heads littering the compound. Unfortunately, we don't really know where they came from. The photo journalist notes "sometimes he goes too far and forgets his people", so perhaps the apparent wantonness of the slaughter is to some extent actual. However, this could also be the opposite of modern warfare where the victims are never seen as death is delivered at a distance. Here "the horror" is displayed, nothing is hidden. Interestingly, this seems insane, and yet it is the truth of things, the truth of war, and beyond that death is a truth of life, something long acknowledged by Buddhism.

The Sattipatana Sutta, where the Buddha laid out the essentials of mindfulness practice, includes a cemetery contemplation. At the time of the Buddha the yogis would go to actual cemeteries and sometimes live there for extended periods of time. Often the dead bodies were not buried or burned but just discarded, left in cemeteries, out of compassion for the animal kingdom, for vultures and other animals to eat. So yogis would observe the human body in various states of decomposition and work with what that brought up in themselves. The whole point for these yogis was to see that whoever this body belonged to had been subjected to the same law that they were subject to.

(Rosenberg, 1997)

Rosenberg also says, "Meditation on death and cemetery contemplation are still done in the forest monasteries of Asia." (1997).

Kurtz notes, "It is impossible to describe what is necessary to those who do not know what horror is." Kurtz seems to conceive of himself as a philosopher/king/warrior, but is he such, or has he set himself up as a servant of "the horror"? Is there a context in which the necessity he appeals to is real once he has effectively left the military? Where he sits is a logical progression from his understanding of war, from his honesty and clarity of insight, from his ability to act, to do what is necessary. But in the service of what?

Buddhism does not necessarily advocate pacifism. Henepola Gunaratana (1991) distinguishes between genuine compassion and "idiot compassion", where the genuine can be extremely tough in the service of the good, whereas "idiot compassion" is some sort of fuzzy wuzzy new age thing that is imprecise, often inconsiderate in terms of the larger whole, and which can ultimately lead to more harm than good. Clarity of insight, mindfulness, and awareness are all worthy virtues within Buddhist thought and practice, but Kurtz seems to have gone beyond simple clear awareness of "the horror" and become quite attached to it, and ego-involved. He has 'made friends' with it, entered into a personal relationship with it, and this attachment and ego-involvement are hardly Buddhist virtues. His necessity is unnecessary, his conduct reprehensible, and while I would not go so far as to say that he was insane, he is morally accountable for his actions and Willard's execution of him is just, and even compassionate in the genuine sense.

In killing Kurtz, Willard adopts the mantle, becomes the dark Buddha. There is something of the sacrifice of the king motif from Frazer's The Golden Bough (1959), emphasized by shots of the sacrifice of the bull intercut with shots of Willard killing Kurtz. This is associated with the myth of the dying and reborn king, with Willard in the role of the king reborn. He is a better one than Kurtz, however, as he knows to throw down the sword once necessity has been served. As the dark Buddha he sees and accepts "the horror" without being attached to it. His action is compassionate. When he throws down the sword his followers follow suit and cease to be his followers, though what they do with their freedom is up to them. The collective spell is broken.

Willard does not subscribe to the lies of the military which serve to cover "the horror", but neither is he enslaved by it. Rather, he finds a middle way. The final dissolve is from him to the stone Buddha at the left of the screen. The camera on him pans right such that his image superimposes with that of the Buddha. Compared to the former association with Kurtz, it is a better fit.

©1998, Eric Pettifor

text inlude err: may not exist

References

Coppola, Francis Ford. 1979. Apocalypse Now (VHS). Omni Zoetrope.

Gunartana, Henepola. 1991. Mindfulness in plain English.Wisdom Publications: Boston.

Paranjpe, A.C. (1993). Style over substance: The loss of personhood in theories of personality. Paper presented at the sixth annual conference of the Western Society for Theoretical Psychology, Banff, Alberta, October

Rosenberg, Larry. 1997. Death Awareness. Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Fall, 1997.